Maud Powell (1867–1920) and George Gemünder (1816–99) were trailblazing figures – she the first American-born violinist to be recognised internationally as an artist of the first rank, he a German-born immigrant who brought top-level European violin making to the United States. They lived in an era when both women and new violins were considered ill suited to the upper reaches of the music world, and yet by a strange twist of fate, Powell became the first major violinist ever to use a new violin as her primary concert instrument. How this came to pass is both a cautionary tale and a study in ironies. By all appearances it was a swindle whose victim ended up with the violin she loved most. It was also an inadvertent blind test of the sort no ethical researcher could ever mount.

I first heard about Maud Powell through the writings of her biographer Karen Shaffer. In 1986 Shaffer founded the Maud Powell Society for Music and Education. In 2014 Powell received a lifetime achievement award at the Grammys. Among her many accomplishments were U.S premiers of the Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, and Dvořák violin concertos. Powell was born in Peru, Illinois, and began playing violin and piano when she was seven. Her family took her to hear the celebrated French-born violinist Camilla Urso, and as Powell later remembered, “She showed me what all my crude scrapings might become.” Powell was soon recognised as a prodigy. At 13 she went to Europe and studied with Schradieck, Dancla and Joachim, who conducted the Berlin Philharmonic for her debut.

There is a George Gemünder violin with a typewritten label added above Gemünder’s. It reads: ‘Property of Miss Maud Powell.’ According to Shaffer, this is most likely the instrument Powell took with her to Europe. She returned with a Pietro Guarneri of Venice, which Joachim had chosen for her. Though she would keep it for two decades, the violin was evidently not a fit, because she soon began shopping for another. Perhaps because she was no longer under Joachim’s wing, perhaps because New York was well behind Paris, London and even Chicago in terms of violin expertise, Powell was besieged by fakery.

Powell with the Peter Guarneri violin chosen for her by Joachim

A New York dealer called Victor S. Flechter sold her an instrument supposedly built by Gaspard Duiffopruggar in 1515. After Powell had struggled with it for two years, the violin was identified by maker Henry R. Knopf as a cheap French copy. Powell sued Flechter. George Gemünder was among the expert witnesses. The press had a field day, but in the end Powell prevailed. (Flechter would later be convicted and briefly imprisoned on charges of stealing the 1725 ‘Bott’ Stradivari. George’s brother August Gemünder reportedly testified against Flechter, having mistaken a Strad copy Flechter was selling for the original ‘Bott’. When the original was recovered eight years later, Flechter was exonerated. Such was life in New York.)

Powell’s next instrument came to her on loan as a Nicolò Amati. According to an unpublished memoir by her husband and manager, Godfrey Turner, it produced “what we all knew as the ‘Powell tone’ [though at a] sacrifice of energy too sad to contemplate.” Her next acquisition was more fortuitous. Now in her mid-thirties, in full flight as a soloist, and flush with money after an international tour with John Philip Sousa’s band, she purchased the 1731 ‘Mayseder’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. Two years later, she bought a Giuseppe Rocca to go with it. Thus equipped with two Italians – one about 180 years old, the other scarcely 50, Powell may well have felt her search was over. Then one day in 1907 she and Turner visited a New York dealer called Oswald Schilbach, who said, “I have the violin for you.”

Maud Powell with “Mayseder” Guarneri del Gesu

He told them it was a Guadagnini, made in 1775. The pristine condition and brightly coloured varnish came as “rather a shock to her,” Turner later wrote. Powell had understandable concerns about authenticity, but according to Schilbach the violin had lain in a trunk “somewhere in the West” for 75 years, and he had recently replaced its original Baroque neck with a longer one. An article from Musician News (August 1908) provides the backstory: Schilbach was approached by a ‘German pedlar’ named Simsen, who showed him a dirt-encrusted violin, which Schilbach recognised as a J.B. Guadagnini. Instead of simply buying it, he found a third party to pay Simsen $300. Schilbach then bought it from the third party for $270. The paper notes this was ‘rather a complicated method of carrying out a simple transaction’. At any rate, Schilbach offered Powell the violin for $4,000. He agreed that she could take it on tour with her, and that if she decided to purchase it, could pay on her return. Powell’s enthusiasm for the violin grew as the tour progressed, but in the end she had to settle a lawsuit in order to finish the transaction. In her absence, Schilbach had sold it to a higher bidder.

Maud Powell with her “Guadagnini”

“You simply can’t appreciate how beautiful it is,” Powell wrote of her new violin. “Look at its big broad chest under the bridge. No hollow, caved-in consumptive lines there that tell of the ‘one-lunger’.” Her Guarneri was a “deeper-toned” violin with a sound that came “more from within the instrument.” She compared it to “a capricious woman who had to be cajoled.” Of the Guadagnini she said, “He is a strong lusty youth, and I can thrash him.” With its “glassy clearness, its brilliant and limpid tone quality, [it was] better adapted to American concert halls.” She played the Guadagnini for the rest of her career.

Powell died from a heart attack while she was preparing for a concert in 1920. She was just 52. Her husband later loaned the violin to the young French violinist Renée Chemet, who was then finishing her first American tour. Chemet seemed elated; in a pamphlet called The Truth about Maud Powell’s Violin Turner reported her sentiments: “For the first time in my life I will be really happy in my work! To play with my other violin, it was like a singer who must make a career with a bad throat. Now – now I have the throat of a Caruso!”

The violin was later purchased from Powell’s estate by one Nathan E. Posner. When he decided to sell it, he engaged Ernest Doring of John Friedrich & Brother in New York. In 1926 the violin was sold to Henry Ford – an amateur fiddle player, collector of all things American, and at the time the wealthiest man on earth. Doring signed a certificate describing the violin as “a genuine example in all essentials.” Some two decades later it was included in his now-classic book, The Guadagnini Family of Violin Makers.

Ford had a small fleet of violins. These included the 1744 ‘Doyen’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, two Strads and a Bergonzi. According to Ford executive Bruce Simpson, who as a boy had had the chance to play the violins, Ford “liked the sound of [Powell’ s] violin very much and it was used regularly by his fiddler to play for the Early American Dances which were a favourite pastime for Mr and Mrs Ford.” After Ford’s death in 1947 the violins were transferred into the collection of the Henry Ford museum, but it was not until the 1970s that expert appraisals of the instruments were commissioned. Kenneth Warren examined Powell’s violin and in a letter to the curator wrote, “[It] bears no actual relation to a genuine G.B. Guadagnini.” It was, he believed, made by George Gemünder between about 1860 and 1870. If so, Powell had come full circle, for the Gemünder she played as a student was made in 1869.

Sharon Que in her Ann Arbor workshop with Maud Powell’s violin

I first saw Powell’s violin on a sunny afternoon in September, 2015. The Henry Ford had engaged Ann Arbor restorer Sharon Que to bring its violin collection into playing condition. Knowing of my interest in Powell’s instrument, Que called to say it was in her shop. My first impression: no way was this a Guadagnini. It was not even an especially sophisticated copy, compared with some of the work being done today. But I suppose each generation’s copies leave the next generation smiling at the gullibility of its forebears. By chance, Que had in her shop violins by George Gemünder, his son Herman, and his brother August. She felt strongly that Powell’s violin was part of the family. Holding Powell’s violin in one hand and a George Gemünder in the other, I thought the two might have been varnished one after the other from the same pot. Kenneth Warren cites the “yellow–pink varnish characteristic of Gemünder.” I like Powell’s description: “Gold dipped in blood.”

I spoke to James Warren, the current proprietor of Kenneth Warren & Son, who said his grandfather was quite sure of the attribution – and had said so many times. Kenneth Warren began working at Wurlitzer’s in New York in 1925, and so had ample chance to see Gemünder’s work. I also spoke with the violin expert Philip Kass, who has written articles on Gemünder and is planning a full biography of the maker. Kass is hesitant to credit Gemünder, given that no other Guadagnini models by him are known. Moreover, Gemünder documented the models he worked with, and Guadagnini is not among them. Kass does not rule out Gemünder, but wants to re-examine the instrument before drawing any conclusions. Neither Kass nor Warren – nor, I suspect, any experienced violin maker – would now attribute Powell’s violin to Guadagnini.

“George Gemünder has not only gained the same results as those achieved by Stradivarius and others, but he has sketched a better acoustic principle for producing tone. It is for this reason that August Wilhelmj, the great violinist, calls George Gemünder the greatest violin maker of all times, for Wilhelmj had learned by ample trial of the instruments made by George Gemünder that they were incontestably all that the latter claimed for them.” Or so wrote George Gemünder in his self-published memoir, George Gemünder’s Progress in Violin Making. It makes a peculiar and depressing read. Blatant self-aggrandisement is interspersed with stories of violinists, including some the greatest of his day, who mistook his copies for originals, and then lost interest when they learned who had made them. Camilla Urso’s father together with her teacher once visited Gemünder in search of a Guarneri for Camilla. Gemünder showed them a violin. “Both were very much surprised at it,” he wrote, “not only on account of its undoubted genuineness, but also that it was kept so well.” When he told them he had “perpetrated a joke,” and that he himself had made the instrument, they continued their search elsewhere.

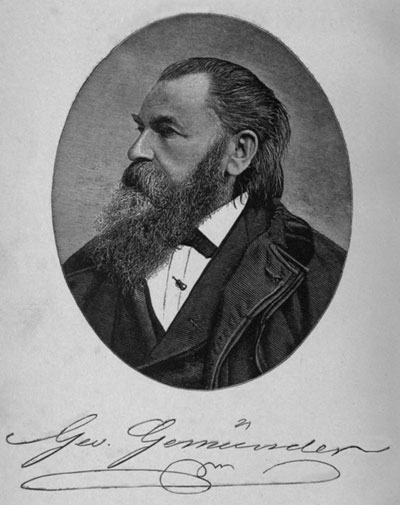

Gemünder was born and raised in southern Germany. He moved to the US in 1847 after four years working for Vuillaume in Paris. According to James Warren, ‘The fact that Vuillaume hired him says a lot about Gemünder’s talent, because Vuillaume had the pick of Europe’s craftsmen.’ Vuillaume had apparently warned Gemünder of the risks of moving to a continent where the art of violin making was not fully understood and appreciated. Gemünder went anyway. After struggling to establish himself in Boston, he moved to New York City in 1850. There his career blossomed. Two decades later, no doubt feeling secure in his success, he relocated to Astoria, New York (now part of Queens). Kass credits this move away from the city for the subsequent downward drift in Gemünder’s fortunes. He suffered a disabling stroke in 1889, and his death a decade later left his family bankrupt.

According to Turner, Powell’s “encounters with domestic and newly made violins had left her with an unfavourable impression of their merits. One bow stroke on a shiny new violin once provoked her to exclaim, ‘It’ s a beast!’” She was no doubt influenced by prevailing beliefs, though to be fair, she could be equally hard on old violins. “Do you know,” she wrote, “the fine ‘Strads’ and ‘Amatis” of the world have almost reached tone bottom, and that the Guadagninis and Bergonzis are about the only instruments of today that have good, solid bodies?” She describes playing “one of the most famous of all Strads.” As she started to bow gently, “its tones startled me with their strange, weird beauty.” But when she began to “draw heavily across the low strings […] tone power and beauty suddenly vanished.”

Who made Maud Powell’s violin? With further research violin experts will no doubt reach a consensus. The question of whether she was deliberately swindled is harder to answer. It is tempting to imagine Gemünder yielding to frustration and passing off one of his copies as an original, but there is absolutely no evidence for this. Though his memoir shows an unappealing side to his personality, he was a highly respected member of the international violin community. Besides, he died eight years before Powell’s crucial meeting with Schilbach. To my mind, Schilbach was at least partly guilty. It’s easy to believe he was taken in by a Guadagnini copy that fooled Ernest Doring. It’s impossible to believe that he purchased the copy with a Baroque neck.

The most interesting question remains unanswerable. What if Powell had discovered her beloved Guadagnini was, well, ‘a beast’? When the legal battles were over, would she have continued to play it? Would she have gone a step further and championed Gemünder’s work? By all accounts she had the courage of her convictions, so I like to think the answer is yes. Schilbach did get one thing right: it was the violin for Powell. It was, she said, “the one perfect thing.”