“How comes it then that the violins are so unlike each other? How comes it that one sounds powerful and the other weak?” This was Leopold Mozart in his 1756 treatise on violin playing. Having expressed admiration for a Society for Musical Science founded in 1736, he regretted that it was “never given timely and generous support. The whole realm of music would never have been able to repay such a society if it had succeeded in kindling so clear a light for instrument makers…”

It is only recently that science has begun to answer many basic questions about the violin and our perceptions of it. Doing so frequently calls for blind-testing, a methodology that originated late in Leopold Mozart’s lifetime, and has since transformed any number of fields, from psychology and medicine to wine-tasting and snack-food development. Even symphonic music has been affected: It was the widespread adoption of blind auditions in the 1970s that helped women gain a foothold in professional orchestras. Over the past two centuries, numerous blind tests have pitted old violins against new. Though results frequently favored the new, few minds were changed – at least until recently.

In January 2012, Hughes Borsarello, a French violin soloist with a deep love for Old Italian instruments, read about a double-blind study conducted in an Indianapolis hotel room. Twenty-one players had tested three new violins against two Strads and a Guarneri del Gesu. The most-preferred instrument was new, and the least-preferred was a Stradivari. Borsarello was exasperated. A hotel room? You need a concert hall and an orchestra to show what a great Old Italian can do. And it’s not enough to use just any Strad or del Gesu – you need excellent examples in top playing condition. He was hardly alone in his reactions. Strad players such as Frank Almond, James Ehnes and Stephen Isserlis blogged on the study’s supposed inadequacies. Borsarello, however, went a step further than other critics: He called French scientist Claudia Fritz and offered to help create a better experiment.

The Indianapolis study had been organized at short notice and without funding by Fritz, Fan-Chia Tao and myself. Though we doubted the results would be reversed by a larger study, we were eager to push ahead with the research, and so Fritz got back to Borsarello. Planning soon began on what would become the largest experiment of its kind ever mounted.

Nine months later, ten violin soloists joined a team of scientists and researchers in the affluent Paris suburb of Vincennes for three days of testing. Instruments by some fifteen contemporary makers arrived in cases and shipping boxes. Thanks mainly to Borsarello and his friend Thierry Ghasarossian (a violist and dealer), a dazzling assortment of Old Italian violins appeared. These included six Strads, all from his Golden Period or later, and two Guarneri del Gesu violins, both from the 1740s. All had been set up and adjusted by expert hands. To prevent any possibility of tampering, Ghasarossian took charge of the old violins, and I the new. Our job was to monitor the instruments throughout the experiment. Neither of us was permitted contact with the other’s instruments, except under direct supervision.

Time constraints allowed for testing just twelve violins – six old and six new – so we ran preliminary blind tests to winnow down the numbers. Two violinists who were not subjects in the experiment played the instruments for a small group of researchers, players, makers and dealers. Everyone got to vote. Fortunately, there was good agreement on the final selection, though the conversation did heat up when we realized that neither Guarneri had made the cut. As it turned out, violins by six contemporary makers would go up against five Strads and another Old Italian.

Six old and six new violins were selected in a preliminary blind test Photo: Stefan Avalos

The primary task of the soloists was to choose the violin best suited to replace their own for an upcoming (and hypothetical) concert tour. Each soloist had a 75-minute private session in a rehearsal room, then another in the Auditoreum Coeur de Ville, an elegant, wood-paneled concert hall renowned for its acoustics. (Though it seats just 300, it is relatively long and narrow, and gives the impression of a much larger space.) We asked the soloists to use their own bows, and to wear darkened goggles. Otherwise, they were free to test violins as they saw fit. Their first job was to eliminate any that seemed clearly unsuitable. This left the bulk of their time for choosing and then ranking their four favorite violins. They played them with and without piano, used their own instruments for reference, and were able to get feedback in the hall from a listener of their own choosing. All agreed that test conditions were adequate to the task.

Violinist Ilya Kaler warming up before round one of the blind tests. Photo: Stefan Avalos

Though blind-testing is by nature repetitive and untheatrical, the experiment was not without drama. Suspicions arose that a great old violin had been smuggled in with the new. Borsarello was called in to inspect them but found no imposters. In the middle of one session, an entire TV crew burst into the hall and began filming. Running the experiment was so all-consuming that Fritz, Tao, and I began to feel like subjects in a sleep deprivation study. David Griesinger, an expert on concert hall acoustics who was there as an advisor on how to record the experiment, more than once cooked us midnight meals after nearly foodless days.

Of the many qualities attributed to Old Italian violins, perhaps the most mysterious concerns projection. Erick Friedman once told me, “I want a violin with an intimate sound – fifty feet away.” Common sense suggests that the more sound an instrument makes, the better it will be heard at a distance. Old Italian violins are often described as being relatively quiet under the ear, and yet capable of out-projecting apparently louder new instruments. We devoted our last day in Vincennes to investigating this paradox.

Subtle differences between two violins become clearest when listening to a brief excerpt played on each instrument in quick succession. Assessing the relative projection of a set of new and old violins means listening to every possible new-old pairing this way – preferably several times over using different excerpts and different players, with and without orchestra. So time-consuming is the process that we limited ourselves to three old and three new violins. We used the two Strads that had been the favorite of at least one player. Our third choice was no-one’s favorite, but according to acoustical measurements it had the highest overall sound output of any of the Old Italians. We used the three most popular new violins, two of which had been the favorite of at least one player.

Photo: Stefan Avalos

When the day came, an orchestra set up onstage behind an elongated screen, while some fifty invited listeners – including players, makers, acousticians, and audiophiles – sat down with pencils and score sheets for almost three hours of concentrated listening. Violinists Yi-Jia Suzanne Hou, Ilya Kaler, Tatsuki Narita, and Giora Schmidt did most of the playing, though, Marie-Annick Nicolas, Elmar Oliveira, and Solenne Païdassi were also involved. The event closed with a champagne reception, and later that evening there was a farewell dinner for the researchers and soloists. By the following day, we had all gone our separate ways.

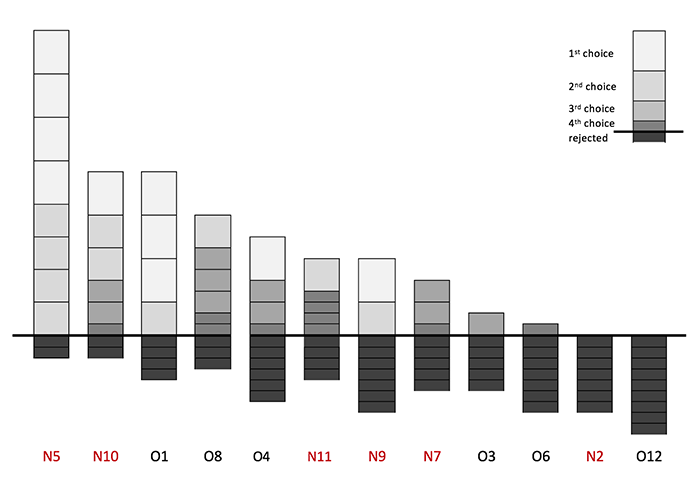

In May 2014, the first paper on the Paris experiment was published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. It dealt with player preferences. A second paper focusing on the listener’s perspective appeared in 2017. As with the Indianapolis experiment, the most-preferred violin in Paris was new, and there was a general preference for new violins. Figure 1 shows how often each violin was chosen or eliminated by a soloist. Tastes clearly vary, for even the most popular violins were eliminated outright by at least two players. Still, three violins dominate the chart. A new violin known as N5 was the favorite of four players, and was otherwise the most popular instrument. The Stradivari O1 was the favorite of three players, and eliminated by four. The new violin N10 was the favorite of only one player, but was included on more top-four lists than O1, and eliminated just twice.

Figure 1: The number of times each violin was a soloist’s first, second, third, or fourth choice, and the number of times it was eliminated. “N” indicates a new violin, and “O” an old.

We had asked each soloist to evaluate several violins (including their own) for timbre and loudness-under-the-ear. On average, the old violins were rated more highly for timbre than the soloists’ own violins, seven of which were old. The new violins were rated more highly still. On the other hand, the old violins were on average less loud under the ear than the soloists’ violins, while the new were significantly louder. Would the loudest instruments project best in the hall, or would the somewhat quieter Strads live up to their reputation and prevail?

According to the listeners, N5 easily out-projected O1 – indeed all three new violins out-projected all three Strads by a solid margin. O1 scarcely out-projected the least-preferred new violin and the least-preferred Strad. We got the same results whether testing with orchestra or without. Moreover, the same results were later obtained by subjects listening to recordings made with a pair of microphones about three meters from the soloists.

The word “loudness” is a neutral term when used scientifically, but in everyday English it can have negative connotations. It is seldom a compliment to be told that your dress or your friend or your violin is loud. On the other hand, loudness-under-the-ear seems a reasonably good predictor of violin projection. N5 was the loudest and the best-projecting of all violins that had been rated for both. O1 was the loudest and best-projecting of the Strads. Players looking for an instrument with outstanding projection should evidently expect a good deal of sound under the ear.

The credibility of these results depends in part on whether the Old Italians we used can be considered worthy examples of their kind. There is no easy way to establish this. The dealers, makers, and collectors who brought them presumably believed in their merits, and they certainly had both the incentive and the opportunity to optimize set-up and adjustment. Remember, however, that whether the Old Italians can be considered top-notch or merely run-of-the-mill, the four soloists who chose Strads each chose a violin with less projection than any of the three most popular new instruments. Perhaps these soloists were uncomfortable with how loud the new violins sounded under-the-ear. Perhaps they overestimated the projection of the old. Perhaps they believed that projection wasn’t everything, and that sheer tonal beauty could count for as much in a hall.

This last possibility we found intriguing. Do listeners prefer the violins they hear best, or does preference depend primarily on the quality of the sound? Some months after the Paris experiment, NHK television producer Kojiro Yamada contacted Fritz about collaborating on a blind test that would be part of a documentary on Stradivari. After much discussion on how to balance the scientific with the telegenic, NHK agreed to a two-part event: a formal blind-test involving listeners in the hall, and a less formal test involving an onstage panel of experts. All this would take place in the Great Hall of Cooper Union during MondoMusica New York in March 2013.

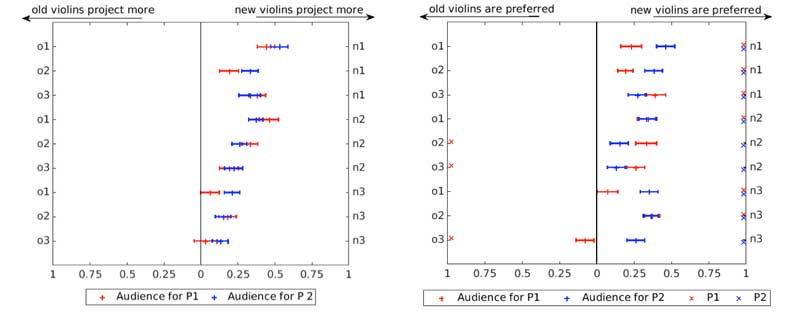

The formal experiment was structured much like the Paris projection test, with three new violins and three Strads, except that all excerpts were unaccompanied, and half the roughly eighty listeners judged projection, while the other half judged preference. (Roles were reversed in successive rounds.) The soloists were Elizabeth Pitcairn and Giora Schmidt. The clear similarity between the two graphs in Figure 2 reflects a strong correlation between projection and preference, at least at a group level. Though more research is needed, we expect this correlation to hold with any group of violins, new or old. Players looking for an instrument that best serves most listeners should evidently place projection well above age on their check-list of desirable attributes.

Figure 2: Listener evaluations of projection (left side) and preference (right side) on a 0-1 scale.

Our impressions and judgements of things can be dramatically affected by what we know (or think we know) about them. Just ask someone who has discovered his Picasso or his Strad is a fake. At a finer level, research has shown that our beliefs shape our perceptions at a basic, neurological level. Understanding this does not neutralize the effect any more than knowing something is an optical illusion makes the illusion go away. It is not a question of snobbery or pretention – it is part of being human. Consider now the near-universal belief that violins improve with time and playing, and that Old Italian instruments – especially those played by great artists – have acquired an extra dimension to their sound, a dimension that new instruments necessarily lack. Given the implications for violinists, it seems worth asking whether these beliefs reflect an objective difference in acoustical behavior between old and new violins. The decisive test is to ask experienced players and listeners to distinguish new violins from old under blind conditions. If they can, objective differences exist. If they cannot, it may be time to reconsider our beliefs.

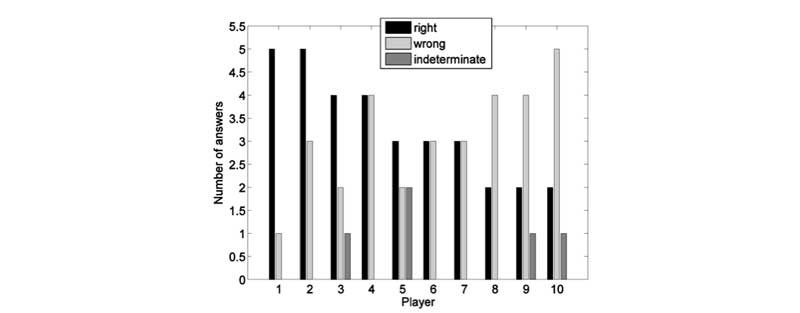

To this end, we asked each Paris soloist to play and then guess the age of a series of new and Old Italian violins, including their favorites. Figure 4 shows that one soloist got five of six guesses correct, while another got five of eight wrong, and the rest were somewhere in between. In all, just 48% of the guesses were correct. These are results one would expect from tossing a coin. Since all the soloists had played Old Italian violins for extended periods, it is hard to argue that inexperience muddled their judgements. Test conditions could have had an effect, except that under these conditions soloists readily separated violins they liked from those they did not, and otherwise made fine distinctions regarding timbre and playability. It is hard to argue that the only quality obscured by darkened goggles is Old Italian sound.

Figure 3: Soloist’s guesses about the age of test violins. Of the 69 guesses made, 33 were correct, 31 were wrong and five were indeterminate. (Answers like “19th Century French” were considered indeterminate.) Just 48% of all guesses were correct.

To see if listeners were any better at telling old from new, we asked seven soloists to each play a one-minute concerto excerpts with orchestra. Unbeknownst to the listeners, the soloists used their own violins. (It might otherwise have been argued that the players were insufficiently acquainted with the test instruments to bring out their individual qualities.) About 84% of the audience thought the first violin was new. It was old. About 76% thought the next violin was old. It was new. Guesses were thereafter rather evenly divided. In total, just 45% of all guesses were correct.

Should we be surprised by these results? After all, the Indianapolis experiment and numerous other blind-tests have suggested as much. Listen online to the test organized by the BBC in the mid-1970s, in which Isaac Stern, Pinchas Zukerman, and Charles Beare were asked to identify a Vuillaume, a Strad, a Guarneri del Gesu, and a new violin after hearing excerpts played behind a screen by violinist Manoug Parikian. The best anyone did was two out of four. Watch the French documentary, “Mystery of the Stradivarius,” where two music critics, two violinists, and a violinmaker tried to identify a 1782 Stradivari amidst three other violins played behind a screen by two blindfolded soloists. All five listeners picked a new violin. Listen to their reasons for doing so.

Then there is the NHK documentary, “Stradivarius: Mysteries of the Supreme Violin.” In part-two of the New York event, a panel that included well-known dealers and makers listened to excerpts played behind a screen on eleven new violins and three Strads. The panelists were asked to evaluate the instruments by various criteria, and then to identify the Strads. In the documentary we are told that “not a single judge could accurately identify all three.” Omitted is the scene where the names of the instruments are read out in order of overall preference, and the first Stradivari shows up nine names down.

The above are recent examples. For a broader perspective, I spoke with Harvard music historian Emily Dolan, who is currently studying the testing of musical instruments through the ages. When I asked her about violins, she replied without hesitation, “I have yet to find a rigorous test in which new violins did not come out on top.”

Has the time come to reconsider our beliefs? Do we really want another generation of players believing a violin’s playing qualities are mainly determined by its age and provenance? Do we want another generation of makers believing their instruments will not reach tonal maturity until long after they are dead? And if we do, should we not provide evidence?

The extraordinary visual and tonal appeal of the best Old Italian violins is indisputable. There is no objective evidence, however, to suggest their achievements should be considered some sort of upper limit to what the violin can do. The fact that no single maker since the 1700s has demonstrated the originality and influence of a Stradivari or Guarneri del Gesu makes it easy to underestimate just how far the violin has evolved in less celebrated hands. Most violinists do not play ‘period’ instruments, and so most Old Italian violins have been extensively modified just to keep them in play. New violins have the advantage of being built for the job, and a growing body of evidence shows just how well they can do it. Leopold Mozart would be glad there is finally “so clear a light for instrument makers.”